What is a “mulatto” in Nirvana’s song ‘Smells like Teen Spirit’?

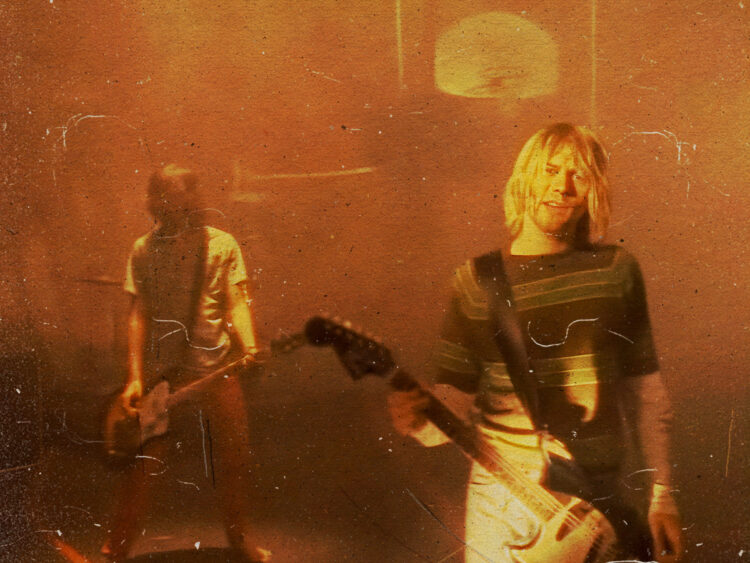

The album Nevermind is the pinnacle of Nirvana’s commercial and critical success in part thanks to the immediacy of its songs. From the opening guitar strums of the lead single ‘Smells like Teen Spirit’, the record is filled with catchy hooks and lyrics aplenty.

Yet some of the lyrics are definitely easier than others to grasp. How about “I travel through a tube and end up in your infection” from the song ‘Drain You’ for bizarre? Or “When I was an alien, cultures weren’t opinions” from ‘Territorial Pissings’ for profound-sounding but completely opaque?

‘Teen Spirit’, too, is full of confounding turns of phrase, not least the title itself. We now know that Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna was responsible for coining it after the deodorant brand she and Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain’s girlfriend had recently discovered. There’s one particular word in the song’s lyrics that most of its listeners likely won’t have come across before.

Two-thirds of the way through the chorus, after singing “Here we are now, entertain us” for a second time, Cobain adds, “a mulatto, an albino, a mosquito, my libido”. The first one of those terms, “mulatto”, will sound completely foreign to most ears.

That’s partly because it is foreign, at least to native English speakers. The word is a slave-era term originating from Spanish and Portuguese “mulato”, used to refer to people of mixed racial heritage.

Is “mulatto” an offensive term?

‘Teen Spirit’, too, is full of confounding turns of phrase, not least the title itself. We now know that Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna was responsible for coining it after the deodorant brand she and Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain’s girlfriend had recently discovered. There’s one particular word in the song’s lyrics that most of its listeners likely won’t have come across before.

Two-thirds of the way through the chorus, after singing “Here we are now, entertain us” for a second time, Cobain adds, “a mulatto, an albino, a mosquito, my libido”. The first one of those terms, “mulatto”, will sound completely foreign to most ears.

That’s partly because it is foreign, at least to native English speakers. The word is a slave-era term originating from Spanish and Portuguese “mulato”, used to refer to people of mixed racial heritage.

Is “mulatto” an offensive term?

The word may even be an adaptation of the Latin word for mule (“mulus”), implying that anyone it refers to is a mix between a horse (the animal ridden by landed gentry) and a donkey (the animal used by slaves). It suggests that multi-heritage people are the result of “mixed breeding”, supporting racist and unscientific ideologies that were widespread while the slave trade was still prevalent.

Indeed, even after the abolition of slavery, being of mixed heritage during the era of segregation in the Southern United States meant facing the sharp end of discriminatory laws. Historic social caste systems implemented during the colonial era of Latin America based on racial categorisations have resulted in residual prejudices against mixed-race populations that continue to this day.

As such, the word “mulatto” has highly offensive connotations. This is particularly true in Cobain’s home country, the United States, where the history of slavery looms large over the political landscape. In fact, it has been considered outdated and inappropriate to use since the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

Why did Kurt Cobain think it was OK to say “mulatto”?

So why would Kurt Cobain, a self-proclaimed anti-racist who castigated those not “standing up against racism”, use this term in his biggest song? Cobain even attacked other bands like AC/DC and Led Zeppelin for using apparently racist lyrics. Was he not guilty of the same thing here?

misinterpretation. More than that, it could be offensive to those who have historically been victims of the term and could be weaponised by unapologetic racists.

But we shouldn’t overlook two things about Kurt Cobain’s songwriting: the layers of irony he adopted in his lyricism and the deliberate lack of attention he paid to the words in his works.

In a 1993 interview, he complained about people always wanting to read into his lyrics, which he described as “garble, just garbage”. He explained that the words of his songs were “stuff that would just spew out of me” and that lyrics were typically the last part of a track he’d write in a hurry out of sheer laziness.

Was he being ironic?

Just because this was Cobain’s approach to lyrics, however, doesn’t mean we should discount them. The fact that they would “spew out of” him actually made them a window into his thoughts and feelings. And, deliberately or not, he displayed a rare ability to employ poetic devices in his own singular style.

If we look closely at the four unusual terms he juxtaposes in the ‘Teen Spirit’ chorus, we see they stand in paradoxical opposition to one another. “Mosquito”, a tiny insect known for buzzing around and parasitically living off the blood of other animals, is ostensibly opposite to the macho solidity of the male “libido”. This seems to reflect either Cobain’s own self-esteem issues in relation to his own libido or his hostile sentiments towards macho culture.

In the same way, the phrase “Everyone is gay” from the In Utero single ‘All Apologies’ isn’t really using the word “gay” as a pejorative slur as it initially appears. It’s reflective of Cobain’s view that puritanical heterosexuality is merely a social construct and a flippant put-down of the gun-toting misogynist Nirvana “fans” he lampoons in ‘In Bloom’.

Likewise, the juxtaposition of “mulatto” with the word “albino”, which refers to a person lacking skin or hair pigmentation, isn’t intended as a slur against anyone. Rather, it’s shorthand for Cobain’s identification with all those who’ve historically been social outcasts regardless of colour.

For the same reason, he refers to himself as an “alien” in ‘Territorial Pissings’. As a teenage runaway who suffered an abusive childhood, he empathised deeply with society’s oppressed and marginalised. And so, for him, different “cultures weren’t opinions”. They were real things to be recognised and respected.